Everyone in the video game world is talking about the enormous–and surprising–breakout success of Baldur’s Gate 3, an ostensible sequel to a series whose last installment was released more than 20 years ago. Someone recently asked me, if they are enjoying Baldur’s Gate 3, should they also play Baldur’s Gate 1 and 2?

It’s a tricky question to answer, for two reasons. The first reason is that despite being a sequel, the lineage of Baldur’s Gate 3 runs through quite a bit of recent and not-so-recent cRPG history. The other reason is Baldur’s Gate II has loomed so large in the cRPG space for so long, that defining what a “sequel” to Baldur’s Gate II would even be is not straightforward. There have been a dozen sort-of sequels to Baldur’s Gate II already! And those “sequels” are themselves part of Baldur’s Gate 3’s lineage.

To understand this tangled relationship, we have to start at the root of the tree: Dungeons & Dragons.

Dungeons & Dragons

The great grandfather of everything in this chart is Dungeons & Dragons, first developed in 1974 by Gary Gygax and David Arneson. “D&D,” as it has become known, is the now world-famous tabletop RPG system played by millions all over the world. It has spawned at least five major “editions” that represent major rule changes, produced one major direct spinoff/competitor, changed corporate owners multiple times, and—most importantly for us—provided the basis for a lot of video games. Today it is owned by Hasbro as part of Wizards of the Coast.

The influence of Dungeons and Dragons on video games can be felt both directly and indirectly. Indirectly, a whole genre of RPGs were created on computers and later video game consoles that utilize progression systems and quantifiable stats that represent capabilities of player (and non-player) characters. This kind of influence is so enormous that it is almost invisible today — it feels like virtually every major game today has some kind of numerical progression system. Major early franchises like Ultima, Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, Gauntlet and Elder Scrolls were in many ways attempts to translate Dungeons and Dragons into digital-native systems. But these series themselves have gone on to influence dozens of other games. Today skill progression systems can be seen in games as far apart as The Sims to Elden Ring to the Zelda series.

Beyond the indirect influences, though, D&D has also been a direct source for a large number of video games. This is surprising because, until very recently, the rules for the various D&D editions have never had video game implementations in mind. At best video games were an afterthought, but most likely they were simply never considered at all. The rules for D&D are designed to foster flexible group-centric storytelling (albeit mainly for combat-centric stories.) Rulebooks will often tell you flat out to “make it up as you go” or “ignore the rules at will” — allowances that are either impossible or unsatisfying in computer games to-date.

Going through every influenced-by-D&D video game on Wikipedia is an exercise I will leave to the reader. However, two major influences on Baldur’s Gate 3 stand out: the Ultima series and the previous Baldur’s Gate games themselves.

Major Influences

Ultima

Ultima was an early attempt in the 80’s by one “Lord British” to recreate a D&D-like game on personal computers. (“Lord British” is not British at all, but a Texan by the name of Richard Garriott.) There were nine total “major” Ultima games, although some of these were broken up into “Part One” and “Part Two” installments, so the actual number of games in the series is quite large. (It also spawned an early successful MMO named Ultima Online in 1997 which I guess is somehow still operating.)

The major reason to care about the Ultima series today is the influence it had on the now popular Divinity: Original Sin games by Larian, who would go on to make Baldur’s Gate 3. Ultima VII in particular was notable for the huge interactive world and immense player freedom. Players could take any object from any house, characters had specific schedules and routines that players could take advantage of. Here’s a brief Wikipedia excerpt explaining this:

The gameworld of Ultima VII is highly interactive: virtually everything not nailed to the ground and not excessively heavy can be moved, taken, or interacted with in some way. It is possible, for instance, to bake bread, to forge weapons, to play musical instruments, to paint a self-portrait, and to change a baby's swaddling by dragging and dropping things in the game world. The Avatar and his companions, if not fed regularly, will complain of hunger pangs and severe thirst, and will even perish if these matters are not attended to eventually. If they come across a disgusting or gruesome scene, they may groan and vomit; sufficient intake of strong alcoholic beverages will also result in visible nausea.

Ultima VII allows free exploration of the game world, featuring a main plot and several other major subquests and tasks for the player to complete. It is a markedly open-ended game, where following the main plotline is inessential to the purposes of enjoyment, exploration, and character advancement — once the player is free from their starting location of Trinsic, a walled city. The Black Gate is highly nonlinear; although there is a linear storyline, this is countered by the ability to explore the map in any order when coupled with the many subquests.

Today, the Divinity: Original Sin games are the most prominent carriers of Ultima VII’s player agency torch. (Or they were, until Baldur’s Gate 3 arrived.)

Divinity: Original Sin and Divinity: Original Sin 2

For nearly 15 years the Ultima series was considered dead. But in 2014, a German developer named Larian Studios brought the ethos back to life with Divinity: Original Sin and its much-lauded follow-up Divinity: Original Sin 2. Larian was quite open about the intention to re-create Ultima VII in their Kickstarter pitch for Divinity: Original Sin:

Picture a modern version of a world not unlike that of Ultima VII, explored either alone or with a friend, that sees you engage adversaries in tactical turn-based combat reminiscent of the great turn-based RPGs of the past. A world that is filled to the brim with choice and consequence situations, reactive NPCs, and a considerable amount of surprises. A world that captures the feeling of playing pen and paper RPGs with our friends. Then add the new stuff...

Anyone who has spent a bit of time playing either of the Divinity games and also Baldur’s Gate 3 should immediately be able to see the similarities: they are built on the same engine, which means the immediate playfeel of the games is similar. More importantly, many of the gameplay mechanisms are nearly identical. The combat, the elemental and environmental interactions, even minor things like digging for buried treasure, even minor things like hotkey bindings — all these elements are translated directly from the D:OS games into Baldur’s Gate 3.

The Divinity: Original Sin games can be described as wacky, fun adventures with complex environmental combat. Besides the impressive commitment to play agency, they also became known for making turn-based combat popular again in cRPGs. Turn-based combat had been mostly abandoned in cRPGs for many years, due in part to the massive success in 2000 of a game called Baldur’s Gate II by then-small studio named BioWare.

Baldur’s Gate and Baldur’s Gate II

The influence of Baldur’s Gate and Baldur’s Gate II on Baldur’s Gate 3 might seem obvious. It’s a sequel, right? Well, yes, but not quite.

Baldur’s Gate and especially Baldur’s Gate II were breakout hits for a fledgling studio called BioWare in the late 90s/early 00s. BioWare today is one of the big names1 in RPGs thanks to major hits like the Mass Effect and Dragon Age series. But back then, they were a small, scrappy studio with one great idea: combine the user interface of real-time strategy games, the gameplay rules and systems of Dungeons & Dragons, and the scripted storytelling from JRPGs into one huge experience. The result was the Baldur’s Gate games.

Baldur’s Gate was not the first translation of D&D into a computer game, but it was certainly the most successful when it was released. BioWare’s major innovation in the first Baldur’s Gate game is incorporating elements from real-time strategy games such as WarCraft II and Command and Conquer. (It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time when real-time strategy games were considered one of the biggest genres in gaming.)

This union between real-time gaming and D&D was not immediately obvious. D&D was an explicitly turn-based system, complete with using “initiative” to determine turn order. In some ways, it was the very opposite of a real-time video game. Even ignoring the turn order, D&D requires players to make careful, tactical decisions and choose from among dozens of spells. Wouldn’t this be overwhelming in a real-time system?

BioWare handled this conflict by utilizing what is now known as a “real-time-with-pause” mechanic. Essentially the game presents as real-time game to the player, letting them click on a map and see their character walk there immediately. But behind the scenes, the game still tracks equivalents of turns, dice rolls, and timing.

Imagine you select the “attack” cursor and click an enemy, your character satisfyingly walks up and whacks the goblin on the head. But if you click a second time, you might be surprised to see a delay—your character stands there and waits a few seconds before taking a second swing. This is because the first attack represented your character’s “turn.” Your next action won’t occur until every other character has taken an action within the timing window.

It was perhaps an awkward marriage of mechanics, but it worked. Baldur’s Gate was enough of a success to spawn a sequel.

The first Baldur’s Gate had been a mostly conventional story with some interesting dialogue trees about an ancient evil that lurked and…caused steel to break? It had a dramatic opening, but was largely forgettable. The companions you could recruit were one-note caricatures, and half of them were joke characters. (Actually, the whole tone of Baldur’s Gate is surprisingly absurd, with fourth-wall-breaking jokes and parodies of RPG conventions.)

Baldur’s Gate II turned up the dial on everything. There was more dialogue, more voice acting, bigger environments, more quests, more options. It even let you import your character from the first Baldur’s Gate so that you could keep your stats and equipment. It dumped you right in the action, introduced you to a villain right away, and dove deeper into your companion’s backstory. It spanned much more of the D&D lore as you traveled down to the Underdark and up to the planes and into castles and dungeons and more.

And, oh yeah, you could, uh, date your companions Aerie and Jaheira. (Perhaps the most lasting legacy of Baldur’s Gate II is the expectation among cRPG players that the player will be able to date/bang some or all of their companions.)

Baldur’s Gate II was a decent, but not huge, sales success. The cRPG genre is and was too niche for even the best games to be hits on the level of Mario or Final Fantasy. But Baldur’s Gate left an enormous mark on the genre. It received widespread critical acclaim for its writing and won many awards. It established BioWare as a pre-eminent RPG studio and real-time-with-pause as a standard D&D-in-the-computer-mechanism. It also set precedents that would live into RPGs for years, including robustly-written party companions, and established a norm that your companions must have voice actors (and maybe be date-able.)

You can see traces of BG2 all over BG3: in the dramatic plot introduction, in the light comic side-quests, in the companion design and even, yes, in the general horniness of the latter. (It’s hard to imagine being able to fuck a bear-druid today if you hadn’t been able to “cuddle under the stars” with Jaheira in 2000.)

The BioWare successors: Neverwinter Nights and Dragon Age: Origins

After the breakout hit of Baldur’s Gate II, a 2D isometric game based on D&D 2.5 mechanics, BioWare immediately pivoted to its internal successor: a 3D game based on D&D 3rd edition mechanics. This was to be Neverwinter Nights, a game built partially as a showcase for the content creation toolkit that came packaged with it. (BioWare would hand off the Infinity Engine to Black Isles to continue to release isometric games—see below.)

Neverwinter Nights was, in some ways, a step back from BG2. Party companions were much more rudimentary, as the emphasis was much more on multiplayer and user-generated content. Neverwinter supported multiplayer sessions where one person could act as a DM and other players could connect and bring in their characters. This meant jettisoning some of the detailed dialogue trees and companion-centric storytelling from BG2. However, it further cemented the real-time-with-pause gameplay approach as the BioWare house style, inching BioWare in a more action-oriented direction.

After Neverwinter and a handful of expansions were released, BioWare moved on again to its next successor game: Dragon Age: Origins. This time, BioWare decided to build their own mechanics and lore from scratch, having decided that paying for the D&D license was no longer necessary for success, and that they had outgrown it. (In a parallel to the previous pivot, Neverwinter Nights 2 would be built by Obsidian Entertainment, the home of Black Isle refugees.)

Dragon Age: Origins, in 2009, was the pinnacle of a certain kind of Baldur’s Gate II successor game. Following the BioWare logic of “keep increasing the production values,” Dragon Age felt like a then-modernized version of Baldur’s Gate II. The combat was an evolved version of Neverwinter Nights RTwP-in-3D. The story was a blend of grimdark Game of Thrones fantasy with some of the light-hearted elements from Baldur’s Gate.

But what stands out today, and what Baldur’s Gate 3 borrows liberally from, are the camp and the cinematics. Dragon Age: Origins utilized the same technology that Knights of the Old Republic and Mass Effect used to make every single conversation feel cinematic. Mostly this means close-up camera angles, detailed character models, and lots and lots of animation and voice acting.

Dragon Age: Origins also featured a “camp” the player could visit any time between dungeons. While at camp, the player would mostly chat up their companion characters (four of whom were bangable in awkwardly-animated sex scenes.) The camp was also how you changed your party members.

Today, this camp exists as…well, the camp in Baldur’s Gate 3.

The Dragon Age series continues on in two more games by BioWare, but it’s really Origins that has the most influence on Baldur’s Gate 3.

Minor Influences

The Black Isle games

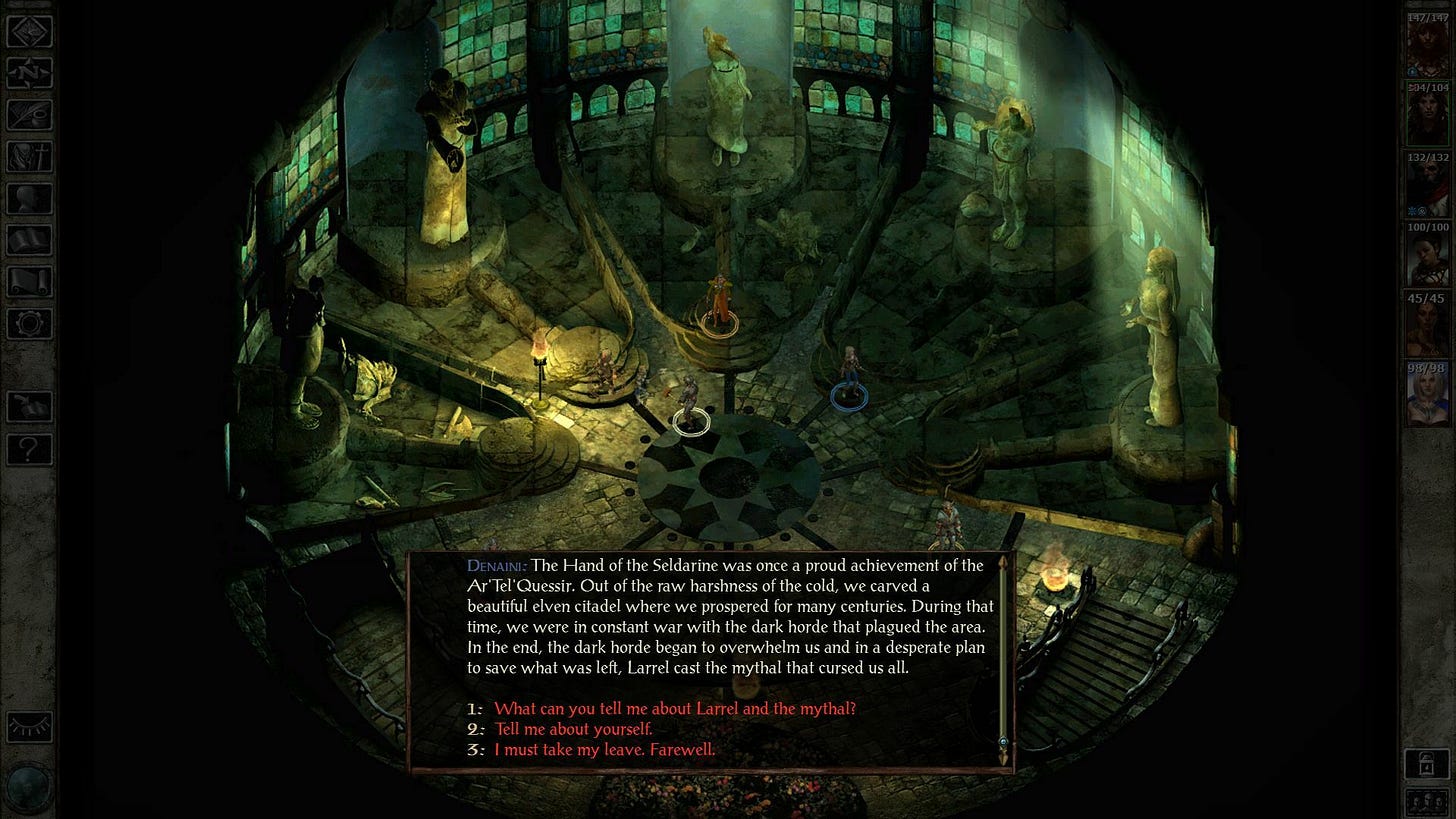

While BioWare was busy translating their RPG mechanics into three-dimensions and non-D&D format, another studio was happy to continue releasing D&D games using the successful Infinity Engine that BioWare pioneered and then licensed. That studio was Black Isle.

Black Isle released three Infinity Engine games. These included Icewind Dale and Icewind Dale II. The Icewind Dale games were more streamlined, combat-heavy versions of Baldur’s Gate. The most notable difference from the Baldur’s Gate series is that in Icewind Dale, the player creates all six members of their party as custom characters. There are no companions, no companion quests or dialogue. You’re all the companions. This is an older RPG concept that many early games had—it pops up in Baldur’s Gate 3 as “hirelings.”

Planescape: Torment was a more talky, philosophical game that is remembered for its many dialogue options and player choices. It’s not a major influence on Baldur’s Gate 3, but you do have a Gith companion in both games. Today you can see strong traces of Planescape: Torment in the dialogue-centric post-Soviet masterpiece Disco Elysium.

Obsidian Entertainment and Pillars of Eternity

When Black Isle closed, a group of former developers founded their own studio Obsidian Entertainment who went on to become a niche RPG studio. Although today they are known mostly for Fallout: New Vegas and The Outer Worlds, one of their earliest games was Neverwinter Nights 2, a sequel to BioWare’s Neverwinter Nights. A decade after that, they would launch one of the first successful Kickstarters for a large-scale “Infinity Engine”-style game, which would eventually become Pillars of Eternity.

Pillars of Eternity and its sequel Deadfire are a different kind of successor to the Baldur’s Gate and Infinity Engine games than some of the other games mentioned here. They eschew the D&D system and lore for home-grown alternatives2. The mainly try to honor the playfeel of Baldur’s Gate II by using a similar graphic style and interface, and the real-time-with-pause (RTwP) combat system. Think of this series as an homage to Baldur’s Gate as a computer game, not as an homage to Dungeons & Dragons or any particular story elements.

The influences on Baldur’s Gate 3 are slight. The broad use of skills in dialogue options, and some of the UI innovations. Primarily, the Pillars games proved out the Kickstarter model for cRPGs that Larian would also use for Divinity: Original Sin.

Owlcat and the Pathfinder games

It wasn’t long after Obsidian had launched its “Infinity Engine” revival that others joined the party. A small game developer based out of Russia called Owlcat launched its own take on the Baldur’s Gate successor game. Where Baldur’s Gate was based on D&D 2.5, Owlcat decided to base its games on the Pathfinder system, which itself was spun off from D&D 3.5 rules. It released Pathfinder: Kingmaker in 2018 and Pathfinder: Wrath of the Righteous in 2021, each loosely based on a Pathfinder tabletop module of the same name.

Owlcat also kept the isometric perspective from the Infinity Engine games, brought back the romances from Baldur’s Gate II, and, initially, the real-time-with-pause combat. With Wrath of the Righteous, they took a cue from Divinity: Original Sin and built turn-based combat in the game from the beginning.3 Wrath of the Righteous in particular was noted by critics and fans for both its complexity and fidelity to the Pathfinder ruleset.

Having a second major turn-based cRPG on the market did a lot to legitimize a turn-based system for implementing D&D mechanics. It also created a bridge between Divinity: Original Sin’s turn-based combat and the more direct Baldur’s Gate II successors. (Recall that implementing D&D as real-time-with-pause was one of the major innovations in Baldur’s Gate, and real-time-with-pause stuck with Bioware in some form all the way through the Mass Effect and Dragon Age games.)

The Pathfinder mechanics were tweaked D&D mechanics. The Pathfinder games proved you could make a successful turn-based game that was faithful to the mechanics of Pathfinder. It was immediately clear the same would be possible with D&D mechanics. Meanwhile, Larian had produced a massive name for itself with the stealth success of Divinity: Original Sin 2 and its vivid companions and storytelling.

The stage was set for these elements to come together.

Baldur’s Gate 3

Fresh off their success with the Divinity: Original Sin games, Larian Studios obtained the D&D license to create a new game based on the D&D 5th edition mechanics, titled “Baldur’s Gate 3.” It is out now, to universal acclaim.

In Baldur’s Gate 3, you can see:

A literal implementation of Dungeons & Dragons

The deep inventory and player agency of Ultima VII

The environmental and elemental systems of Divinity: Original Sin

The goofy humor of Baldur’s Gate

The culmination of the deep companion trends started in Baldur’s Gate II

…and the continuation of the bangable companions trend.

The conversational style and camp dynamics of Dragon Age: Origins

An interface that blends elements of Neverwinter Nights and Divinity

Self-documenting user interfaces as in Pillars of Eternity and Pathfinder

A turn-based combat system based on a tabletop RPG while mimicing the style of a real-time-with-pause game

The results speak for themselves. Many gallons of virtual ink have been spilled singing the praises of Baldur’s Gate 3, so I will not bore you by adding to that chorus. Suffice it to say, a few days after its release, it’s clear that it’s a huge critical and commercial hit.

So…if I like Baldur’s Gate 3, should I play Baldur’s Gate and Baldur’s Gate II?

Maybe! But go in knowing that you’re playing a game more than 20 years old, and that is just one of many sources of the mechanics and ideas you’re loving in Baldur’s Gate 3.

Ten or fifteen years ago, BioWare was the name in cRPGs, but their decline in output since then has been steep.

The systems in Pillars really do echo D&D without copying it. The characters still have attributes and skills, the spellcasters still have memorized spells in spell slots, etc. But they’re different attributes, different skills, and different classes, and during combat the way the math is all calculated is different. Similarly, where D&D games are mostly set in “medieval Europe with more magic,” Pillars is set in “renaissance Europe with more magic.” Deadfire gets more creative with the setting by moving things to an island archipelago that, depending on your interpretation, could be a stand-in for either South Asia or the Caribbean.

Turn-based modes were added later as patches to Owlcat’s Kingmaker and also to Obsidian’s Deadfire.